By Shirley Lyster

If I introduced you to my son Cam, the first thing you’d notice would be his lopsided grin. He was nearly always grinning about something. He had an open demeanour that invited conversation and put everyone at ease. He spoke easily to people of all ages. You’d instantly feel like you could be his friend.

Beneath his jokester exterior lay an insightful and analytical mind. Cam loved to make people laugh, but he could just as easily pick up a serious debate. If he didn’t know something, he’d make sure to learn so he wouldn’t get caught again. And he always needed proof. If you had an opinion, you’d better be able to back it up with evidence.

He lived and breathed hockey from the first time he stepped onto the ice at age five. He was a goaltender who would bark orders to his teammates and wasn’t afraid to use a poke check in an overtime shootout in the final game of the playoffs. After the win, he shrugged off everyone’s disbelief with, “It worked, didn’t it?” He was loud and proud in his support for his team, the Edmonton Oilers. When they signed Connor McDavid, he was sure more glory days for the Oilers were ahead.

His love of music really kicked in when he got his driver’s license. His car had a CD player, but he only owned one CD, so he borrowed some of mine. That led to many late-night conversations about Credence Clearwater Revival, Lynyrd Skynryd, the Allman Brothers, and The Dave Matthews Band. We’d blast 70’s southern rock on our drives to school. Anyone who got a ride from Cam would be introduced to Credence Clearwater Revival. My husband and I once gifted him tickets to see John Fogerty for Christmas. Cam’s favourite song, “Fortunate Son”, wasn’t done well and he was disappointed with that!

A drive to serve

In 2016 Cam was accepted to the Energy Sustainability Engineering Technologist program at Nova Scotia Community College in Middleton, Nova Scotia – a long way from our home in Camrose, Alberta. But Cam was confident and more than ready to be independent.

Within months of landing in Nova Scotia, he joined the Canadian Army Reserves at 36 Service Battalion in Aldershot. He absolutely loved everything about the army (except maybe the food!) and turned his plans around completely. He left college to focus on a full time career in the Canadian Forces.

In the spring of 2017, Cam came home for a visit and let me know that he was having frequent diarrhea. I asked about stress, drinking too often, noticing blood, diet, and the other usual things a person thinks could relate to diarrhea. He answered no to all of them, except that occasionally there was blood. He was busy preparing for his training and promised that if it got worse, he'd go straight to the doctor. He left for basic training at CFB Gagetown and I had sporadic communication with him that summer.

By the end of August, he was seeing more bright red blood in the toilet bowl. He was able to find a doctor, got a referral to a gastroenterologist, and at the beginning of December, he was diagnosed with ulcerative pancolitis. He was given medication and given an appointment for a follow-up.

Cam didn’t let much get him down. He would bounce back from a bad experience with a grin and encouragement for others. ‘Embrace the Suck’ is a popular expression in the army (and now the name of our

Gutsy Walk team!). Cam embraced whatever was thrown at him, even having a strip torn off him by a Corporal for being out past curfew. He was still grinning and having a laugh over it later. He had the power to bounce back from anything. We all expected Cam to bounce back.

A drastic decline

The medication Cam was prescribed lost its effect quickly, and he spiraled into a full-blown flare-up. By the time his next gastroenterologist appointment came around in January 2017, he had lost 30 pounds. His symptoms – weakness, fatigue, the need to be near a toilet – interfered with his work in the Reserves. His diarrhea was worst at night and he had a lot of night shifts. During the day, he was exhausted because he’d been up all night. Food that agreed with him one day wouldn’t the next.

Throughout all this, he tried to carry on his work in the Reserves. But one day I picked up the phone and it was Cam. “The dream is dead,” he said. He made the decision to release from the Reserves and come back home to Alberta where he could be taken care of.

Cam’s brother, Greg, and I flew out to Nova Scotia to help him move. We were shocked by the person who greeted us at the door. Cam was white. There was no colour to his lips, his skin was almost translucent, and his hair was falling out. He was so breathless he could barely make it up a flight of five stairs.

What a relief it was to finally get him in the door of our house. We were sure that this was the beginning of his recovery and felt confident that we could do it together. Mom could fix anything.

The call

It was Sunday, March 19, 2017. Cam had an appointment at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton scheduled for the next day. He was seriously considering having his colon removed and was going to mention it when he got in to see someone. We were behind him as a family if he chose to go that route; we’d do anything to get him feeling better.

Early that Sunday morning, I got a phone call from Cam. He was in the basement, but he couldn’t muster the strength to yell for help. I raced downstairs and found him on the couch, gasping for air, his chest rising and falling rapidly. He whispered that he was having a panic attack. I rubbed his chest and counted for him to try to slow his breaths. He couldn’t.

I called 911. I was on the phone with the operator and Cam jumped up, flailed his arms and legs, and screamed. The operator told me to unlock the front door because the ambulance was almost there. I ran upstairs, unlocked the door, then raced back to the basement. Cam was curled up on the couch and I heard him expel his last breath. A perforated bowel took his life.

No words, no fix

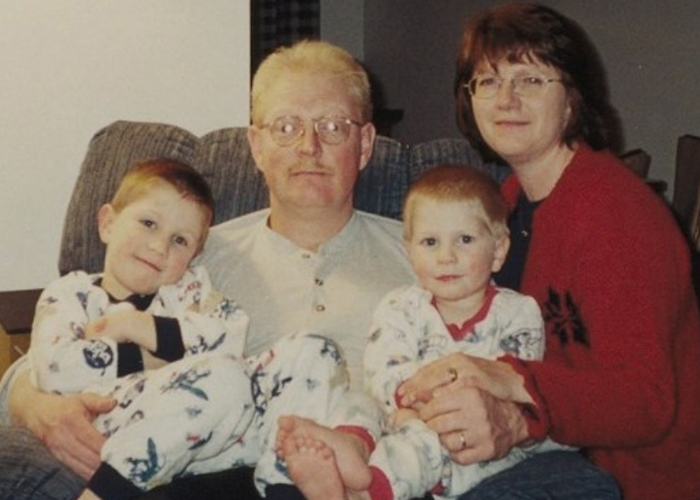

My husband, Bob, and I were married at 30. We had our first son, Greg, when we were 33, and Cam when we were 36. Bob and I were ready for a family and devoted our time to our boys. They were our little world. That world shattered when Cam died.

We’d been this little unit for over 20 years and what are we now? There is no fix for losing a child. There are words for someone who has lost a spouse – widow or widower. Children who lose parents are orphans. There are no words to describe losing your child and there is no way to replicate that unique person you’ve lost.

With Cam’s death, we lost the future we’d planned. We lost grandbabies and nieces or nephews, birthday and holiday celebrations that aren’t tinged with sadness, job successes, and help in our old age. Our son Greg lost his partner in crime, his confidant, and his very best friend. It is with us every day, all day, never far from our minds. We wake up every morning to a day without Cam.

It’s impossible to move on from his death because grief is love, and a parent or sibling doesn’t stop loving their child or brother. The three of us have dealt with it very differently. I can only speak for myself when I say it has been the longest, loneliest road I’ve ever been forced to walk. I am much more selective of what I spend my energy on. I don’t have as much as I used to. I tire easily mentally and physically. I used to be someone who could make a quick decision, now it’s harder. I prefer solitude more than ever. I spend a lot of time watching the sky.

Memories jump out at you when you least expect them. Walking through a mall, I saw a shirt that was exactly the kind Cam would like. My first thought was, “I should get that for Cam.” I left the store in tears.

The music Cam and I both loved was agonizing to listen to soon after his death. But now I listen to the playlists he made almost exclusively. I feel closer to him through the music. In March 2019, a week before his two-year anniversary, I’ll be watching Lynyrd Skynyrd for him.

I couldn’t save him so instead I owe it to my son to bring awareness to the disease that claimed him. That is my mission.

Never, at any time in Cam’s short journey with ulcerative colitis, was he made aware that it could be fatal. I want to change that. I want people to be aware of the seriousness of this illness. It is not “just” colitis. Be vigilant, follow doctor’s orders, and go to the hospital if symptoms worsen. Advocate for yourself and make sure your healthcare team listens. Specialists can be hard to find, so make sure your family doctor knows what’s going on if you must see him or her instead of the gastroenterologist. Be knowledgeable and keep up with the latest developments in research. And, most of all, talk to people about your disease because with understanding comes acceptance.

Cam was a young man that had everything going for him. His commanders in the Reserves saw great potential for leadership in the Army. He was an incredibly selfless man who was always mindful of others. He decided in high school that he wanted to be an organ donor. Little did he know at the time that it wouldn’t be long before his tissues and corneas would help over 40 people.

There’s a saying that a man dies twice; once when his heart stops beating, and again when his name is said for the last time. I hope the name Cam Lyster will continue to resonate and his legacy will be to educate and warn people of the dangers of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Contributions to Crohn's and Colitis Canada advance research, care, and support services so that people living with inflammatory bowel disease can live well and reach their full potential. Make your donation here.